By Stella Joseph-Jarecki (Enquiries: stellamusicwriter.wordpress.com)

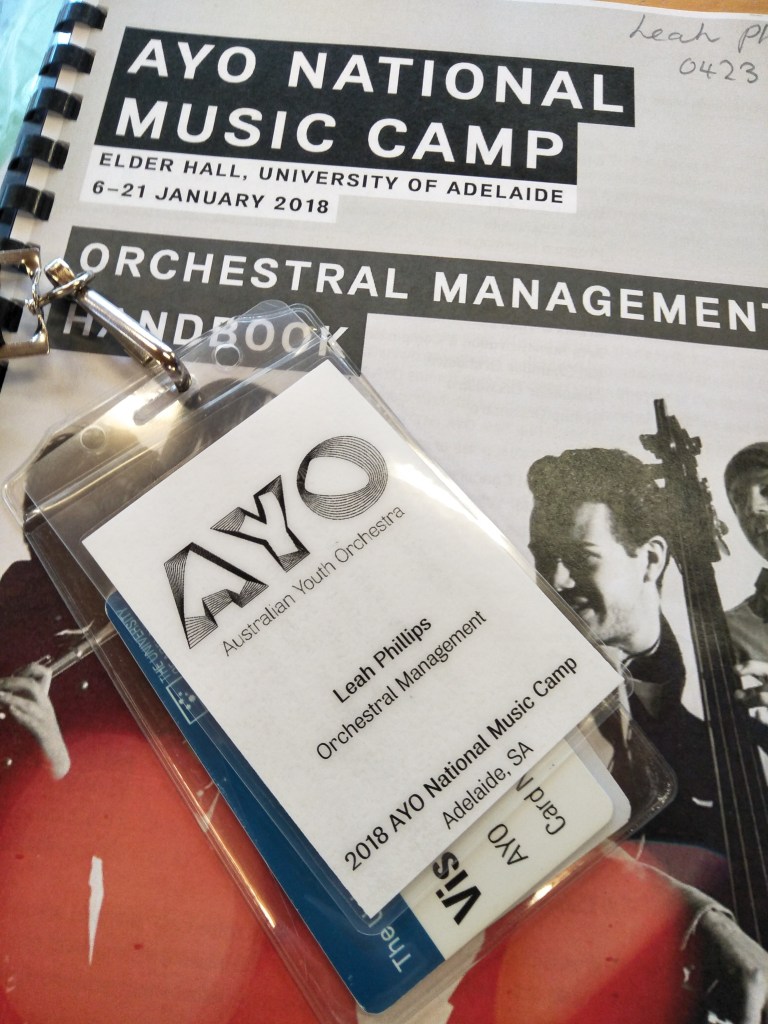

I had the chance to speak to Timothy Mallis, an emerging composer and pianist. Timothy is an experienced music teacher, offering lessons in piano, music theory and composition. If you are interested in online lessons, or would like to keep up to date with Timothy’s work, you can refer to his website, YouTube and SoundCloud.

I know it’s hard to sum up your entire sound world as a composer in a few snappy phrases, but what are some styles and genres that you are interested in?

I think the best way to answer this question is to say, I actually try to separate my influences from my style. The reason is, there are a lot of people and a lot of composers that I am inspired by, but I take it with a grain of salt. I think you can always have elements of really interesting compositional things that you are inspired by, such as the rhythm and harmony of Stravinsky, the theatricality of Britten operas… With all of those things, you can take a piece from each of them, and ask, well how can I take this interesting element and turn it into something that’s still going to be engaging for an audience.

My influences are really anything I listen to- anything from Greek folk music to English choral music. I think that question is quite tricky for most composers because the compositional processes is often very intuitive. How do you come up with a melody? It’s a very intuitive process. When you go back and ask, what were my influences in making that melody, it could be said that it’s everything that you’ve ever listened to, and now it’s become a genesis of something else.

How do you approach balancing teaching and other occupations, with putting time aside for actually writing music?

I work at the Australian Boys’ Choir with a number of different vocal ensembles and choirs. So that gives me an ‘in’ for writing compositions, I write pieces for them to perform. So my routine is really influenced by what they’re doing.

I grew up with the choir, so it has been lovely writing for the training ensembles! Recently the choir had its 80th birthday which was very exciting. I wrote a Sea Shanties medley for a combined training choir as part of the celebrations.

Apart from composing as part of my other jobs, a good tactic for motivating myself to compose, is entering competitions. There are pros and cons with competitions, because they have so much baggage associated with them. You put all the effort into creating something and there’s a competitive air around them… But that being said, it’s a really good thing because you have constraints, and they provide an opportunity for you to compose. And of course, there’s the possibility of a monetary prize or some kind of recording at the end.

I’m actually writing something for a competition at the moment, for St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. As part of their Christmas events each year they premiere a newly composed choral work. We’ve been given a text by Les Murray, Animal Nativity, a very Australian Christmas themed poem which is really nice. Other constraints are the time limit, the choir’s ability, and the fact there is an organ available.

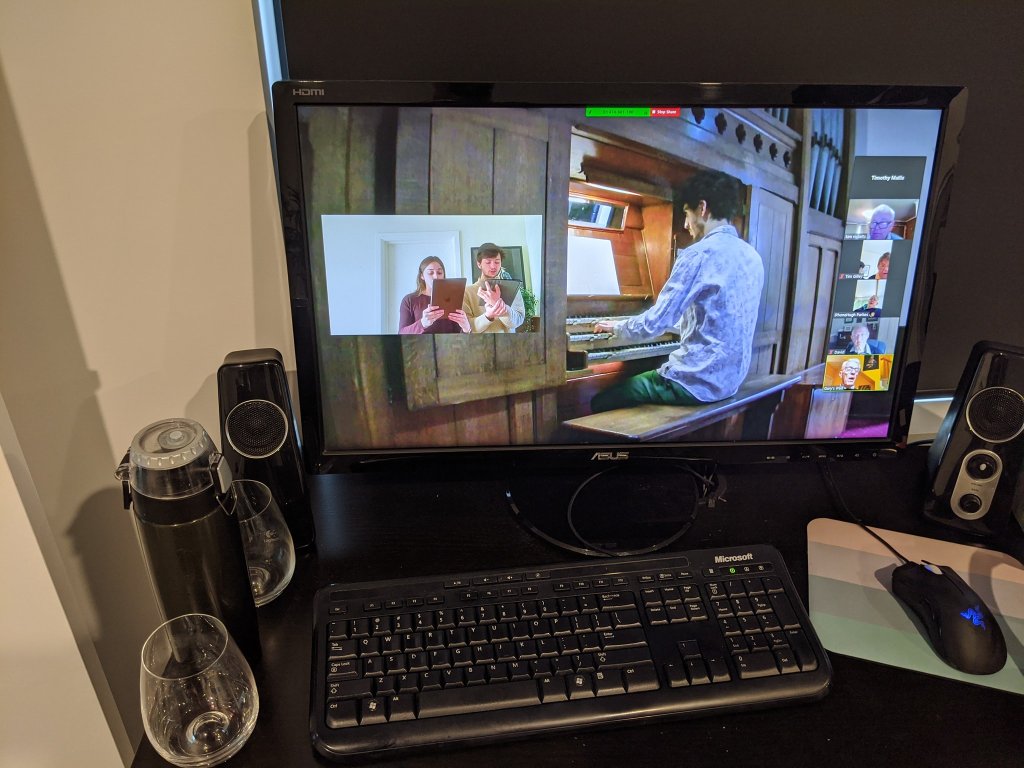

[At the time of interviewing, Tim was in the process of writing his entry for this competition. In the months since, he submitted his piece, and went on to win first prize! His piece was premiered at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney during their A Choral Christmas Celebration concert in December 2019. Although I didn’t end up hearing the work, I was certainly not surprised when I found out this good news.]

I actually find as a choral and vocal composer, it’s not the texts that are the challenge, it’s finding the texts. Finding texts that, a) work for voices and b), actually speak to you. Of course, in addition to having permission to use it or it being out of copyright!

I will only start writing a vocal piece once I have found a text that really speaks to me. My compositional timeline is almost based on the amount of time I spend in the poetry section of bookshops or online. I was in Daylesford a few months ago and found a fantastic series of poems by C. J. Dennis, which I’d love to turn into something. As far as I know, the collection hasn’t been set to music before. That’s another thing, I think it’s important to try to find things that haven’t been set to music before, to bring to life.

Beyond browsing and book shops, which is a very sensible way to find texts, how do you go about finding texts, digging into texts, working out what you might use in your next project?

I’m a sucker for metre in poetry, so I tend to lean towards a particular kind of poetry. Australian Poetry Library is a great online resource. But I find it much more enjoyable just to walk into a bookshop or into a library.

But texts can find their way to you in surprising ways. I once came across a passage from a book by Aristotle. It was such a nonsense piece, and a brilliant look at what we have achieved in the fields of biology and science! It was Aristotle trying to figure out why fish don’t sleep… It was such a bizarre piece of text. But I thought, wouldn’t it be great to take it completely out of context, so I wrote an acapella arrangement of the text for a quintet of singers.

On a more serious note, I am very aware as a white male, there is a potential for cultural insensitivity in the way you approach certain texts. So I stay conscious of that. When it comes to the collaboration side of things, I think it’s important to be open to collaborating with a wide range of people. People who may not otherwise get a chance to be heard, or may be disadvantaged in some way. To not only be open to collaboration, but to actively pursue it.

I was involved in a project organised by the Arts Centre called 5x5x5. It was a collaborative project where five composers collaborated with five poets, to create pieces that were five minutes long. We were assigned the poets. I was really fortunate to work with writer Morgan Rose, who was initially based in the States but now works in Melbourne. Her poem was quite a brutal feminist work and it was really fantastic to work with. That’s another wonderful thing that’s happening in the Australian music scene: social progression through music.

[The Arts Centre has uploaded the pieces from 5x5x5 to their website for us all to enjoy. You can listen to Tim and Morgan’s creation Soapbox here]

What do you think are the essential qualities needed to persevere as a composer? Not to necessarily churn out work constantly, but to hang in there and continue to create, while obviously having other commitments.

Composing is a lot like literary writing. It’s not really that we’ve chosen to do it. It’s something that we have to do, an outlet of some kind. I think part of what keeps us going, is that we would be lost if we didn’t write!

If you’re feeling stuck, I think it’s important to remind yourself why it’s so essential to your being.

How do you approach having different works at different stages of development?

I was taught as a composition student that it’s better to have a few pieces in the works at the same time, ideally at different stages of the writing process, than just work solely on one piece. The reason is, you’re going to have an editing brain, a composing brain, an orchestration brain, maybe also a typesetting brain…

You can always tackle a different part of the composition process. You may be focusing on how the piece looks on the page, or just trying to come up with the initial genesis of ideas. The expansion of the ideas is usually the hardest part of the process.

I suppose time management in that sense, is making sure that you have explored each avenue of your time in your composition time. That helps a lot. That being said, I am a very deadline-oriented person and will finish about 50% of a project in the immediate lead up to the deadline. But I am aware of that, and I know that it helps me to work that way.

How do you see the future of newly-composed, classically influenced works in Australia? Especially in terms of works composed by young musicians like yourself.

I think there are several elements to getting your works out there. One of them is your craft, one of them is the people you know and one of them is the marketing that you can do, how you can actually get your works performed. A lot of focus is on the first two, generally, with young composers such as myself. There’s a sense of craft because we go to university and get some training, and in the process you meet people who might want to perform your works.

But the third element, having your music heard by an audience who might not normally want to listen to it, so not your friends, is the challenge.

I think there is such a value in interdisciplinary performances, bringing together creatives from different areas. Even if a project isn’t a complete success from a craft perspective, there is always the sense that we’ve connected with a new audience who might come to another concert.

While I was still at university, I took part in a project organised by a fellow student Andrew Groch, which was a collaboration between creatives and the Ian Potter Gallery in Parkville. As part of the project, a number of us were able to perform inside the space, works which were inspired by the artworks in the gallery. The first part was more of an improvisatory installation inside the gallery, and the second part was a concert of five pieces which had been written for that specific concert. And a number of people came up to us after the performances and said that they had really enjoyed it, and would not have normally attended a concert like that.

Another good example would be the collaboration between Victorian Opera and Circus Oz, with the 2016 production of Pagliacci (pictured below).